Operations are strictly organised and occur in accordance with fixed procedures. The plant is operated from the control room, which is continually manned by operator teams.

The atmosphere in the control room is calm, allowing the staff to focus their full attention on the process. All meetings (shift changes, team meetings) are functional.

To ensure the plant operates safely under all circumstances, four staff are on duty in the control room at all times: a shift supervisor, a deputy shift supervisor, a reactor operator and a turbine operator. They all have specific duties. The space is therefore divided into four quadrants, each manned by an operator with his or her own tasks and responsibilities. Each of these responsibilities comes with its own instruments and, in one case, documents. The turbine operator has everything he needs to hand in his quadrant, to prevent him having to walk back and forth, ensuring that the situation in the control room remains as quiet and orderly as possible.

All documents are concentrated around the deputy shift supervisor. All the necessary information – including procedures and technical information – are available on paper, and also in digital format.

The nuclear power plant is in continuous operation. It is operated from the control room, which is manned round-the-clock in shifts. EPZ sets high standards for the staff who operate the nuclear plant from the control room. They have at least a professional degree (‘HBO’ level) and are selected for qualities such as ability to cope with stress and ability to work in teams.

When they join EPZ, staff receive eighteen months’ full-time training, including ten weeks at the simulator in Essen, Germany, which simulates all kinds of normal and abnormal conditions. Operators also receive four weeks’ theoretical teaching in nuclear physics at NRG in Petten, as well as practical training in the form of internships in various parts of the company. After eighteen months they take an exam administered by the regulator ANVS. If they pass, they are authorised for two years, after which they are reassessed.

Operators receive continuous training throughout their career. They take a four-week refresher course every year, two weeks of which are spent at the simulator. Every time an employee is promoted, he/she receives further training, which can last as long as a year.

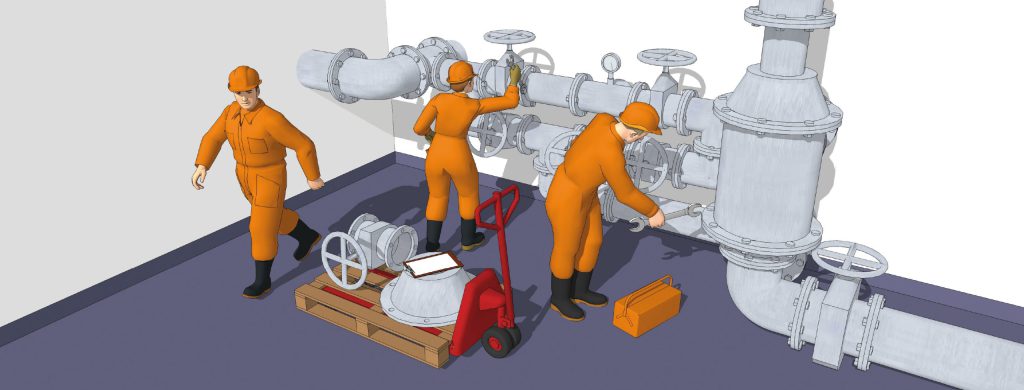

Engineers work outside the control room, in the plant itself, under instruction from the staff in the control room. They have secondary vocational qualifications in a technical subject, and complete six months’ internal training after joining the organisation.

All staff (in the control room and in the plant) have the necessary skills and tools stipulated in documents like Human Performance Tools and Management Expectations. These documents are updated whenever new information becomes available, and checks are carried out to ensure the staff’s knowledge and skills are kept up-to-date.

Oversees the procedural side of operations. Is responsible for nuclear and general safety and commercial operations during his watch. In the event of a technical fault or unusual circumstances, the shift supervisor [1] takes the appropriate measures to ensure reactor safety and coordinates actions in and around the plant.

Assumes an independent position to ensure that daily operations comply with procedures.

The deputy shift supervisor [2] sits beside a bookcase full of written procedures describing normal operations, and procedures to be followed in unusual circumstances.

A special panel allows the deputy shift supervisor to monitor the nuclear plant’s critical safety functions, including conditions in the primary system, the functionality of the containment structure and conditions in the reactor.

The reactor operator [3] monitors the reactor operations. He checks the automatic controls during normal operations, and ensures that any technical fault is dealt with in accordance with the prescribed procedures. If necessary (and prescribed), he intervenes.

The turbine operator [4] monitors electricity production by the turbine and generator. This, in principle, is the non-nuclear side of normal operations. The turbine operator ensures that any technical fault is dealt with in accordance with the prescribed procedures. If necessary (and prescribed), he intervenes.

The shift engineers receive instructions from the control room. They monitor the plant and carry out instructions, tests and inspections.

The commander is a full-time professionally qualified firefighter. The shift of the nuclear plant and the security organisation each provide members of an initial response team who are qualified firefighters. The regional fire service also arrives within ten minutes.

In the event of a major fire, EPZ has a crashtender with foam extinguisher of the type used at airports.

EPZ has opted for the best of both worlds:

- German hardware, the best available nuclear technology, both then and now. German technology is based on automatic operations, keeping the human intervention needed to a minimum.

- Operating procedures that originated in the USA. The American philosophy assumes that humans should always be able to intervene if the situation requires. When and how is precisely defined in procedures. The most important thing is that staff always have the right information, continually monitor automatic operations and only intervene in predefined situations according to a prescribed procedure.

In short: the plant can be shut down safely without human intervention but, if necessary, humans will intervene. In every situation, it must be possible to re-establish a safe situation, either automatically or manually.

The operator team works on the basis of:

- Peer checking: team members never take decisions and actions on their own.

- Specific communication techniques: how and when to give an instruction, how to communicate it.

- Pre-job briefing: before deciding or doing anything, staff discuss the procedure and desired results. This is the moment to clarify any confusion or ask critical questions.

- Self-checks: staff always check the result of their own work and communicate this to their colleagues.

- Situation awareness: staff are trained to be continually aware of the result of their actions and decisions.

- Calm in the control room: the shift supervisor ensures that there is peace and quiet in the control room.

The shift supervisor can call up the emergency response team at the touch of a button. A duty roster ensures that 18 officials from a range of disciplines are on call at all times.

In the event of an alarm, the emergency response team gathers under the management of the on-duty Site Emergency Director, who takes over all responsibility and authority for managing the facility and taking any action needed.

The operation of the nuclear plant remains the responsibility of the shift supervisor, who communicates with the Site Emergency Director. The SED ensures that the emergency response plan is implemented.

Tasks are clearly allocated in the emergency response team. A policy team is formed, and a liaison is sent to the authorities. Strategies, procedures and flows of information are used to categorise the situation, to establish how serious the fault is, and what measures are appropriate.

The emergency services and authorities are contacted via the national emergency response network. Clear arrangements have been made with the authorities concerning how serious incidents should be dealt with. Regular drills are held, including drills for responding to terrorist attacks.

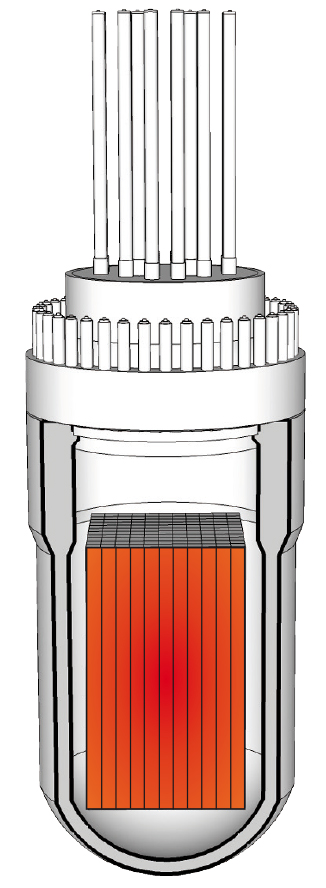

In all circumstances the nuclear fission process can be stopped with one touch of a button. This releases the control rods into the reactor to absorb the neutrons, immediately bringing the chain reaction to a halt.

The automatic control system can also decide to immediately shut down the reactor (SCRAM) if certain parameters or events make it necessary. The emergency button does not then need to be operated manually.

In extreme cases, a standby shift can be called up. There is an auxiliary shutdown control room which can take over control of the nuclear plant if the normal control room becomes unavailable for some reason.

The shifts are backed up by a support department elsewhere on the complex. Staff from this department provide support on operational matters.

Staff work full-time on the improvement of processes, procedures and fault analysis. Faults and failures are analysed and documented. Faults at nuclear plants in other countries are also examined and their implications for operations at Borssele analysed. In this way, we are able to constantly improve our operational experience, and keep it up to date. This allows us to anticipate malfunctions and keep them to a minimum.

When failures do occur, we learn from them. And we share what we have learnt with our fellow operators in other countries.

A reactor core always continues to produce residual heat, even when it is no longer critical. The fuel in the reactor keeps producing heat due to radioactive decay, even though the chain reaction (nuclear fission) has stopped.

The core must therefore also continue to be cooled during any shutdown. The cooling water both shields against radiation and absorbs excess heat. So even if the main systems have to be opened up, auxiliary systems which are operated from the control room are in operation.

The nuclear plant has several cooling systems (see Design) that operate independently. They never shut down simultaneously. The plant’s technical specifications set out which cooling or other auxiliary systems have to be available.

Outage periods are always meticulously prepared for, both for commercial reasons (they must be kept as short as possible), and for reasons of safety, because a balance must be struck between maintenance and operational requirements. Safety is always the main priority. Responsibility for nuclear safety lies with the outage department during the outage period.

In the control room, the rule is that all decisions must be taken conservatively. In the event of a defect, staff in the control can always return the nuclear plant to a familiar state by following set procedures. In unusual operational circumstances, EPZ uses special decision-making techniques. In the event of technical faults or defects found during maintenance, a permanent group of specialists (or their deputies) meet to take decisions in a transparent manner. They analyse and compare data from different perspectives, then identify cause and effect and possible solutions and alternative solutions. They then take a well-considered decision.